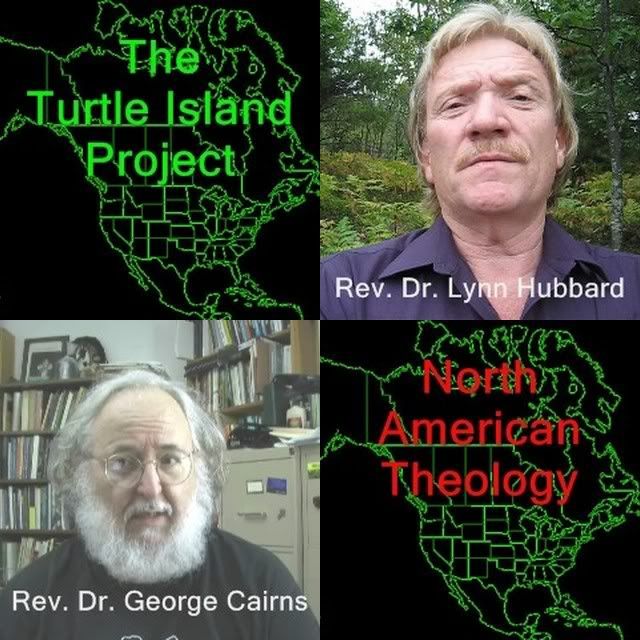

Some Thoughts on a North America Theology

By Rev. Dr. Lynn Hubbard, director/co-founder of the Turtle Island Project

As a child I was raised in a very conservative German Lutheran, tradition.

By the eighth grade, I knew Dr. Martin Luther's small catechism by heart.

I have at one time or another been a member of the MS, LCA, AELC, and ELCA.

In addition, I have had an active life in the ecumenical and inter faith communities, and served as the marketing director for the Parliament of World's Religions.

All of this is to say, that I think I have a pretty good understanding of the theological spectrum of contemporary Christianity.

I assume that many of us in this room share the belief that, Christianity is at a cross roads, a juncture in it’s history, where two distinct paths lie before it.

I assume that many of us in this room share the belief that, Christianity is at a cross roads, a juncture in it’s history, where two distinct paths lie before it.

One leads to a nondogmatic, nontraditional understanding of the faith: normned by the teachings of Jesus, and tolerant of other religions.

This pathway is developing in, with, and under the various grass roots movements of the church, and is often referred to as the church emergent.

The other path way is concerned with circling the theological wagons of dogmatism, confessionalism and fundamentalism.

The other path way is concerned with circling the theological wagons of dogmatism, confessionalism and fundamentalism.

This movement is helping to bring about, what I believe is a disturbing convergence between politics and religion on issues concerning abortion, homosexuality and the separation of church and state.

Often referred to as “Evangelical Protestantism” it’s basic conservative political and religious values are also found in catholic and mainline protestant traditions.

Strange bedfellows, but nevertheless united in the reification of their own religious metaphor, and their intolerance of other religions.

Circling the wagons in this fashion is, I suppose, a predictable reaction from those of us, like myself, who have traditionally benefited from the political structures of the church.

Not only have we enjoyed political power within the church, we have been in the position to determine the very meaning of the Gospel by interpreting it through the eyes of our own Euro-American Christian traditions.

However, today, many of us find ourselves having to share our theological toys with other of God’s children who have different skin colors, genders, languages, sexual orientations, and theological ideologies; ideologies arising from their own communities of origin.

Those who have had power and control of the church, must now scoot over and make room for them in our pews; and maybe, heaven forbid, actually open our ears, and our hearts to their testimony, and to the witness of the love of God in their lives, not just ours.

Steve Charleston, who is a member of the Choctaw Nation and the current Dean of The Episcopal Divinity in Cambridge Mass. Wrote a wonderful article titled “The Old Testament of Native America” in that article he wrote:

"The fact is that Christians must permit the same right for other peoples that they have claimed for themselves. God was as present among the tribes of Africa as God was present among the tribes of America, as God was present among the tribes of Israel. Consequently, we must be cautious about saying that God was unique to any one people; God was in a special relationship to different tribes or in a particular relationship with them, but never in an exclusive relationship that shut out the rest of humanity."

Now we can circle our theological wagons around whatever centers of authority we believe will stop the natural evolution of religious consciousness.

We can act as if we can define and confine God's revelation in Christ to our understanding of scripture and tradition.

We can ignore our God given and revelatory human reason, and confine the living Christ to the archaic cosmologies and tribal hatreds of people living in first century Palestine.

The fact of the matter is that religious consciousness, like the rest of nature evolves.

Historic religious consciousness emerged from pre historic religious consciousness, and today, many of us are living proof of the fact that our understanding of history, as well as our understanding of God is undergoing a radical transformation.

We not only stand on the brink of a communications revolution in this country, but a fundamental spiritual transformation.

Certainly part of that transformation involves the transcendence of traditional Euro-American thought forms, be they philosophical, theological or political.

My own contribution to this transcendence of the spirit, by the spirit and for the spirit, centers primarily on inter faith issues, and specifically on the relationship between Native American religious forms of thought and Christianity.

My interest is both practical and theoretical.

I not only think and write about these issues, but also have the good fortune to have Lakota friends of the Sicangu tribe, who allow me to participate as much as I can, or should, in their life.

Through my relationship with them I have learned more about what it means to be a religious person, than in my academic careers or my years in the Lutheran ministry.

I have learned that spiritual wisdom is not the sole possession of any one people. But rather, wisdom is the recognition of the multicultural and dialogical nature of truth. It is the opening of the heart and mind to the genius and insight of the “other.”

It is a belief that truth will be found within the collective wisdom of our shared religious experiences, and not solely the possession of one particular tribal or cultural revelation.

It is my sincere belief that Christianity must once and for all renounce its religious imperialistic tendencies. That individual Christians must reconsider their anthropocentric anthropologies and rediscover their proper and most natural kinship with all of creation.

In short, we need to developed theologies based on the primacy of nature over history, and the subsequent importance of spatial metaphors for envisioning the God /World relationship.

It is just such theologies which are emerging in the Native American Theological community; and it is by listening to their voices, that the possibility of a new North American Theology can emerge, a theology which is truly multicultural, and dialogical in nature, a theology of this place, North America and for this time, the 21st. century.

No comments:

Post a Comment